Tucked deep inside the mountains of southern Pennsylvania, Buchanan State Forest holds a secret that most people drive right past without ever knowing.

Hidden beneath towering trees and rocky ridges is a stretch of old highway — complete with massive tunnels — that was once packed with speeding cars and is now completely silent.

The Abandoned Pennsylvania Turnpike is one of the most unusual outdoor destinations in the entire country, blending history, mystery, and adventure into one unforgettable trail.

Whether you love hiking, cycling, or just exploring forgotten places, this hidden gem is absolutely worth discovering.

The Forest That Hides a Highway

Most forests keep their secrets well, but Buchanan State Forest might be hiding one of the most jaw-dropping surprises in American outdoor history. Spread across roughly 2,000 acres of southern Pennsylvania, this rugged woodland sits on top of something most visitors never expect to find — a full-scale highway swallowed whole by nature.

The mountains here are steep and the trees grow thick, creating a canopy that hides almost everything beneath it. Roads, structures, and even tunnels vanish into the green.

Buchanan State Forest covers parts of Fulton and Bedford Counties, offering miles of trails, wildlife habitat, and quiet backcountry camping.

But the real draw is what lies beneath the forest floor level — a preserved corridor of old pavement threading through the mountains like a ghost road. Locals have known about it for years, but the wider world is only recently catching on.

Walking through this forest feels different from any other hike because every step carries the weight of forgotten history. The trees may look ordinary, but the road they guard is anything but.

America’s Lost Superhighway

Back in the 1940s, the Pennsylvania Turnpike was considered one of the most modern roads in the entire country. Cars zoomed along at speeds that felt revolutionary for the time, and the highway became a symbol of American progress and engineering ambition.

Today, a 13-mile section of that same road sits completely frozen in time.

The Abandoned Pennsylvania Turnpike stretches between Breezewood and the town of Hustontown, passing through two enormous mountain tunnels. No cars have driven it in decades.

The pavement is cracked and stained, weeds push up through every seam, and the white lane markings have nearly faded into the concrete.

What makes this place so special is how intact it remains. Unlike most abandoned infrastructure that gets torn down or repurposed beyond recognition, this stretch of highway kept its original shape.

Old mile markers still stand along the shoulder. Guardrails rust quietly in the mountain air.

Walking or cycling this road today feels like flipping through a history book that somehow came to life — except quieter, and surrounded by birdsong instead of engine noise.

Built on the Remains of a Failed Railroad

Long before a single car ever rolled through these mountains, the tunnels were already being carved out of solid rock. The story of this corridor actually begins in the 1880s, when a group of ambitious investors launched a massive railroad project called the South Pennsylvania Railroad.

The goal was to connect Philadelphia and Pittsburgh through the rugged Allegheny Mountains.

Dozens of tunnels were planned. Workers blasted and dug through mountains across the state.

Then, just as momentum was building, the money ran out. A legal agreement between competing railroad barons effectively killed the project before it ever carried a single train.

The half-finished tunnels sat abandoned for decades, slowly filling with groundwater and silence.

When Pennsylvania decided to build a modern turnpike in the late 1930s, engineers realized those old railroad cuts were a golden opportunity. Rather than blasting entirely new paths through the mountains, they repurposed the existing tunnels and graded corridors.

The South Pennsylvania Railroad never moved a single passenger, but its bones became the foundation of one of America’s most celebrated highways. Few roads in the country carry such a layered backstory beneath their surface.

The Tunnel Highway Era

When the Pennsylvania Turnpike officially opened on October 1, 1940, drivers were stunned by what they encountered. Seven mountain tunnels stretched across the route, each one a feat of engineering that required vehicles to slow down, switch on headlights, and travel through hundreds of feet of solid rock.

Nothing like it had existed on an American highway before.

The tunnels became legendary. Families on road trips would count them down like milestones.

Truckers learned exactly how long each one took to pass through. Newspaper reporters called the turnpike the “Dream Highway” because it made traveling across Pennsylvania faster and more dramatic than anyone had imagined possible.

The tunnel experience was genuinely thrilling for a generation that had never seen anything like it.

Two of those original tunnels — the Sideling Hill Tunnel and the Rays Hill Tunnel — sit inside the now-abandoned section of road. Both were bored through massive ridges that tower over the surrounding forest.

Visiting them today, you can still see the original stonework around the portals, the ventilation systems bolted to the ceilings, and the faint outlines of the yellow center lines that once guided drivers through total darkness. Engineering history is literally carved into the mountainside here.

Why the Road Was Abandoned

By the 1960s, the Pennsylvania Turnpike had a serious problem. The tunnels that once seemed like marvels of engineering were now creating massive traffic jams.

The passages were simply too narrow to handle two lanes of modern traffic safely, especially when large trucks were involved. Backups stretched for miles on both ends during peak travel periods.

Engineers studied several options. Widening the tunnels would have been extraordinarily expensive and technically challenging — the mountains weren’t going to cooperate easily.

After years of debate, the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission made a bold decision: build an entirely new stretch of highway over the mountains instead of through them.

The bypass opened in 1968, routing traffic along a new alignment that avoided both the Sideling Hill and Rays Hill tunnels entirely. Almost overnight, the old 13-mile section became obsolete.

Tollbooths closed. Workers left.

The gates went up, and the road fell silent. For years, the corridor sat locked behind chain-link fences, accessible only to maintenance crews and the occasional daring trespasser.

What had been one of America’s busiest highways essentially became a 13-mile dead end, slowly returning to the forest around it.

Walking Through Mile-Long Darkness

Stepping into one of these tunnels is an experience that stays with you for a long time. The moment you pass through the stone portal, the forest disappears and the temperature drops noticeably.

Your eyes adjust slowly to the darkness, and the sound of your footsteps starts echoing off the curved concrete walls in a way that feels almost musical.

The Sideling Hill Tunnel runs about 4,727 feet — nearly a mile long. The Rays Hill Tunnel is shorter at around 3,532 feet, but no less dramatic.

Without a flashlight or headlamp, both tunnels become completely black within the first hundred feet. Experienced visitors strongly recommend bringing a reliable light source, and many bring two just in case.

What you find inside is genuinely stunning. Old ventilation fans hang frozen overhead.

Rusted light fixtures line the walls in rows. Graffiti from decades of explorers covers nearly every flat surface, creating an accidental gallery of names, dates, and spray-painted murals.

The pavement underfoot is uneven in places, with puddles collecting near drainage seams. Walking from one end to the other and emerging back into daylight on the far side of a mountain feels like a small but real kind of triumph.

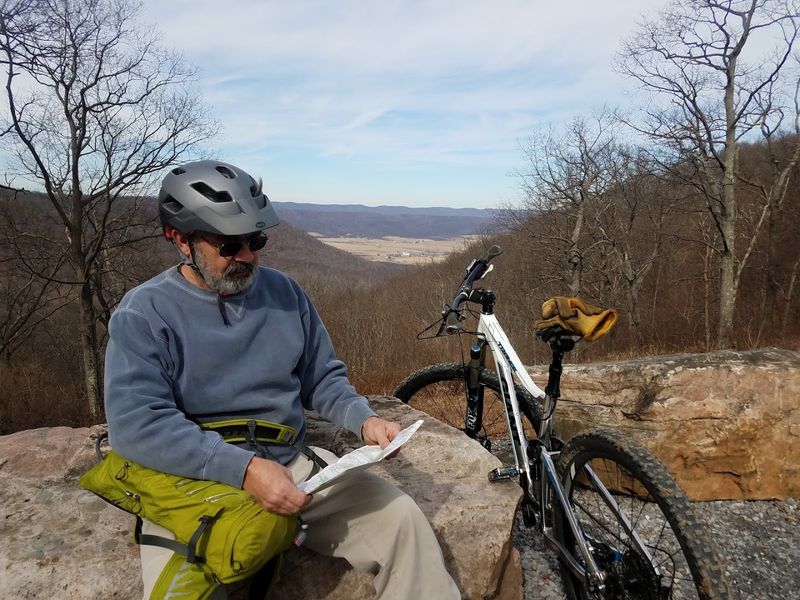

The Pike2Bike Trail Transformation

For decades after the bypass opened, the old turnpike corridor sat in limbo — technically owned by the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission but serving no real purpose. A small group of local advocates eventually started pushing for something better.

Their vision was simple: open the road to hikers and cyclists and let people experience this strange piece of history firsthand.

After years of negotiations, cleanups, and safety assessments, the Pike2Bike Trail officially opened and gave the abandoned highway its second life. The trail runs the full 13-mile length of the old corridor, connecting parking areas on both ends and passing through both mountain tunnels along the way.

It is entirely flat — a rare feature in this hilly region — making it accessible to a wide range of visitors.

Trail maintenance is ongoing, handled by a combination of state agencies and volunteer groups who genuinely love this place. Cyclists can complete the full out-and-back ride in a few hours.

Hikers who take their time exploring the tunnels and roadside details often spend a full day. The Pike2Bike Trail has turned an embarrassing piece of abandoned infrastructure into one of the most talked-about outdoor attractions in Pennsylvania, drawing visitors from several states every season.

A Landscape Packed With Hidden History

The old turnpike gets most of the attention, but the forest surrounding it holds its own remarkable collection of forgotten history. Buchanan State Forest was shaped by multiple eras of human activity, and traces of those periods survive if you know where to look.

The landscape rewards curious visitors who wander off the main trail.

During the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps — a federal work program that employed young men across the country — built camps and infrastructure throughout this region. Stone walls, foundations, and graded clearings from those CCC projects still appear at various spots inside the forest.

Running your hand along one of those moss-covered walls connects you directly to the 1930s in a way that no museum exhibit quite matches.

Older still are the remnants of the failed South Pennsylvania Railroad project — graded embankments, partially excavated cuts, and stonework that dates back to the 1880s. The forest has been slowly digesting these structures for over a century, but they haven’t disappeared yet.

Add in old farmstead foundations, forgotten logging roads, and the turnpike itself, and Buchanan State Forest becomes less of a hike and more of an outdoor archaeology expedition that keeps surprising you around every bend.

A Strange Second Life After Closure

After the gates closed in 1968, the abandoned turnpike didn’t just sit quietly. Word spread quickly among certain communities that a massive, empty highway existed in the Pennsylvania mountains — and people came.

Urban explorers, photographers, and adventurous teenagers found ways past the fences and spent years documenting what they found inside.

Hollywood took notice too. Several film productions used the abandoned corridor as a location, drawn by its authentically decayed atmosphere and the dramatic scale of the tunnels.

The road’s flat, straight surface also attracted military training exercises at various points, with the long tunnel interiors serving as useful simulation environments.

Graffiti artists treated the tunnels as a massive canvas. Over the decades, layer upon layer of spray paint built up on the walls, creating an accidental archive of styles, eras, and personalities.

Some pieces are crude and forgettable. Others are genuinely impressive works of art that could hang in a gallery.

The entire interior of both tunnels is now covered floor to ceiling in color, giving the darkness inside an unexpected vibrancy when flashlight beams sweep across the walls. This unofficial creative history is now as much a part of the tunnel experience as the concrete and rock themselves.

Why It Feels Like a Forgotten World

There is something genuinely hard to describe about standing in the middle of a highway with no cars, no noise, and no signs of modern life in any direction. The pavement stretches ahead and behind you in a perfectly straight line, and the mountains rise on both sides, and the trees press in close, and the whole thing feels like a dream that hasn’t quite ended yet.

Nature is winning here, slowly but unmistakably. Saplings push up through cracks in the asphalt.

Mosses and lichens spread across old guardrails. Sections of the roadway have buckled under decades of freeze-thaw cycles.

Animals use the flat corridor as a travel route, and their tracks appear in muddy patches near the tunnel entrances on quiet mornings.

Yet the big structures refuse to disappear. The tunnels, built to last generations, show almost no structural compromise despite decades of neglect.

The stone portal facades still stand sharp and proud against the mountainside. Old mile markers lean at slight angles but remain readable.

Walking this road feels like visiting a place that time forgot on purpose — a preserved snapshot of mid-century America wrapped in forest and kept cool and quiet by the mountains that always surrounded it.